Internationalization & Localization in Python

In this post, we’ll look briefly into Internationalization and Localization in Python using the GNU gettext library. Localization and Internationalization, often spelt I18N and L10N respectively, while related, are distinct. A simplistic comparison is that I18N often is done by engineers by including support for foreign language scripts, different date formats, number formatting, etc… which in turn allows the program to be localized. Localization includes translation, or even how the the product is perceived in different regions, countries, etc.

There’s a humorous, albeit false, story demonstrating a localization disaster, when Chevrolet decides to release the Chevy Nova in Mexico. The problem is that Chevrolet doesn’t realize that ‘no va’ translates to ‘it doesn’t go’. The Chevy Nova, or the ‘Chevy doesn’t go’ has abysmal sales, until the name is changed. While the story is an urban legend — the word “nova” also exists and has the same meaning in Spanish as in English — there are plenty of real localization problems of which to be mindful.

Greeting Program

For our purposes, we’ll be laying down some internationalization infrastructure to allow our simple program to be localized. We’ll localize our program into Spanish… and glance at Hebrew.

The simple program is called greeting.py and prints out a few lines of text. See the code here.

def greet():

'Prints out greeting message.'

age = 25

print('Hi')

print("What's up?")

print('I am %s years old!' % (age))

print('\n')

greet()

Hi

What's up?

I am 25 years old!

Simple enough. Let’s highlight the procedure we’ll need to follow.

- Mark strings which should be translated as ‘translatable’.

- Extract translatable strings.

- Translate strings

- Switch languages (Use

gettextto ‘get’ string translations)

1. Marking Translatable Strings

So translatable strings are essentially user facing strings. Strings such a comments or variables should generally be left alone. To mark a string as translatable, we place the function _() around it from gettext. So we import gettext and install greeting.

import gettext

gettext.install('greeting')

def greet():

'Prints out greeting message.'

age = 25

print(_('Hi'))

print(_("What's up?"))

print(_('I am %s years old!' % (age)))

print(_('\n'))

greet()

2. Extracting Translatable Strings

At this point there’s no change to the program’s output. Great! Now we can extract each of the translatable strings.

Do do this, we’ll run the Python script, pygettext.py to extract all the strings. See the command below:

C:\Users\$USER\Anaconda3\Tools\i18n\pygettext.py -d greeting greeting.py

Of course your location of pygettext.py will be different, but as you can tell, it’s located in the Tools\i18n folder of your Python installation. After running the utility you’ll see a new file: greeting.pot Examining the file, we see a header, metadata, and the extracted strings, with a blank string below. It’s these blank strings where we set the translations.

# SOME DESCRIPTIVE TITLE.

# Copyright (C) YEAR ORGANIZATION

# FIRST AUTHOR <EMAIL@ADDRESS>, YEAR.

#

msgid ""

msgstr ""

"Project-Id-Version: PACKAGE VERSION\n"

"POT-Creation-Date: 2019-11-23 15:31-0800\n"

"PO-Revision-Date: YEAR-MO-DA HO:MI+ZONE\n"

"Last-Translator: FULL NAME <EMAIL@ADDRESS>\n"

"Language-Team: LANGUAGE <LL@li.org>\n"

"MIME-Version: 1.0\n"

"Content-Type: text/plain; charset=cp1252\n"

"Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit\n"

"Generated-By: pygettext.py 1.5\n"

#: greeting.py:7

msgid "Hi"

msgstr ""

#: greeting.py:8

msgid "What's up?"

msgstr ""

#: greeting.py:9

msgid "I am %s years old!"

msgstr ""

3. Translating Strings

Now this file, greeting.pot would be handed off to a translator to provide the appropriate translations. It’s important to note charset=cp1252\n". cp1252 needs to be changed to utf-8 to avoid rendering issues with non-ASCII characters. I won’t be filling in any of the other metadata for this example. Since our example is small we can just supply the appropriate translations, but on a larger project, a translator might use translations editor such as Poedit.

Note how

%sis used in the translation and strings. Python F-Strings are not supported at the time of writing.

# SOME DESCRIPTIVE TITLE.

# Copyright (C) YEAR ORGANIZATION

# FIRST AUTHOR <EMAIL@ADDRESS>, YEAR.

#

msgid ""

msgstr ""

"Project-Id-Version: PACKAGE VERSION\n"

"POT-Creation-Date: 2019-11-23 09:54-0800\n"

"PO-Revision-Date: YEAR-MO-DA HO:MI+ZONE\n"

"Last-Translator: FULL NAME <EMAIL@ADDRESS>\n"

"Language-Team: LANGUAGE <LL@li.org>\n"

"MIME-Version: 1.0\n"

"Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8\n"

"Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit\n"

"Generated-By: pygettext.py 1.5\n"

#: greeting.py:7

msgid "Hi"

msgstr "Hola"

#: greeting.py:8

msgid "What's up?"

msgstr "¿Qué tal?"

#: greeting.py:9

msgid "I am %s years old!"

msgstr "¡Tengo %s años!"

Language Tags

The next step requires a little knowledge of language tags. A language tag is a two (sometimes three) letter ISO 639-1 designation used to identify a language. For example, ‘en’ is stands for English while, ‘es’ is Spanish. However, for finer gradation if you needed to localize for two regions such as English from the UK vs the English from the US, the locale or region code can be used. For example, en-GB (English of Great Britain) vs en-US. For our purposes, we’ll just be using ‘es’, for a generic non-locale specific Spanish.

Integrating Translations

With our Spanish translations finished and a basic understanding of language tags we can move on. Much like we used the pygettext.py tool to extract translations, there was another tool it the same folder, msgfmt.py. It takes a *.po file as an argument outputs a binary *.mo file. Fortunately our greeting.potfile just needs to be renamed with the *.po extension. Once you rename it, we’ll need to place in a specified folder for gettext to find it.

So let’s lets create a few new directories. From the workspace, add the following: locale/es/LC_MESSAGES and add your newly renamed greeting.po file. Note our language tag, es in the path. Navigate to this folder and run msgfmt.py passing in the new file name sans extension.

python C:\Users\$USER\Anaconda3\Tools\i18n\msgfmt.py greeting

Once you execute this you should have two files in the LC_MESSAGES folder:

- greeting.po

- greeting.mo

4. Switching languages

With the final infrastructure in place we can write a short function that will allows us to change between languages.

Going back to greeting.py, we’ll add a new function that will allows us to switch between languages.

def select_language(language):

lang = gettext.translation('greeting',

localedir='locale',

languages=[language],

fallback=True)

lang.install()

Let’s examen the gettext.translation() method a little closer. localdir is the where our local directory is located in the current workspace. languages corresponds to our language tag, in this case it’ll be ‘es’. By setting fallback=True, if a string requires a translation, but one isn’t available for the corresponding language it’ll return the hard-coded string. In this case English, even though we didn’t set up an ‘en’ language. The following code demonstrates the program language being switched from English to Spanish and back to English. By passing an invalid language tag, it ‘fellback’ back to English.

import gettext

gettext.install('greeting')

def greet():

age = 25

print(_('Hi'))

print(_("What's up?"))

print(_('I am %s years old!') % (age))

print('\n')

def select_language(language):

lang = gettext.translation('greeting', localedir='locale', languages=[language], fallback=True)

lang.install()

# Default language 'English'.

greet()

# Change language to Spanish.

select_language('es')

greet()

# Change language to English.

select_language('en')

greet()

Hi

What's up?

I am 25 years old!

Hola

¿Qué tal?

¡Tengo 25 años!

Hi

What's up?

I am 25 years old!

Glancing at Right-to-Left Languages

Great! We successfully internationalized and localized our program for a Spanish Speaking audience. Unfortunately, not all languages are so easy. Here’s one example, a right-to-left (RTL) language Hebrew: ISO code. he. Right-to-left meaning that the language is (predominantly)written and read from right to left. I’ve gone ahead created and translated a new *.mo file and appropriate Hebrew locale directory. You can see the final code with the Hebrew example.

#: greeting.py:7

msgid "Hi"

msgstr "שלום"

#: greeting.py:8

msgid "What's up?"

msgstr "מה נשמע?"

#: greeting.py:9

msgid "I am %s years old!"

msgstr "אני בן %s!"

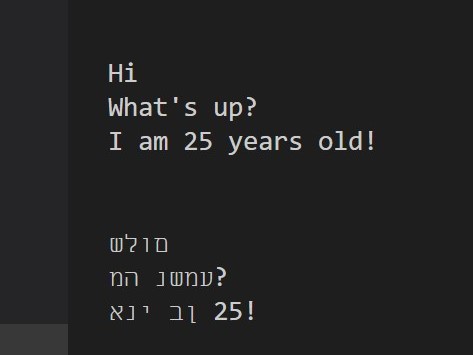

Compare the translations to the terminal output:

At a cursory glance everything may look fine but if you look closer you can see that output from the terminal is backwards! It has rendered a right-to-left language as left-to-right! If copied and pasted into another space, the same backwards text may render correctly, depending on the rendering engine.

In fact, the rendering of the Hebrew in this post and in the *.po will be wrong. Like English, punctuation like the question mark in Hebrew is at the end of a sentence, so it should be on the left side of the sentence, but notice it’s on the right! Note the last sentence also renders incorrectly, “אני בן %s!” It’s roughly equivalent of to “%s years old I am”.

This is what the Hebrew text would look like if rendered correctly:

(Note how it begins on the right side of the page!)

שלום

מה נשמע?

אני בן %s!

Since getting RTL languages to render correctly is beyond the scope of this post, it’s important to take away a couple things. The underlying unicode character order is correct, the problem lies with how they’re rendered. Certain GUI’s may already have build in support and render this text to the user correctly and thus nothing additional needs to be done. If you’re interested in rendering RTL scripts such as Hebrew and Arabic in pure Python, you might consider looking at the BiDi Library. BiDi for Bidirectional.

Final Thoughts

As you can see I18N and L10N is relatively straightforward in Python with gettext—depending on the language ;). The process of localization can be resource heavy especially as a program gains new features, requiring additional translations. We also saw how I18N requires specialized knowledge to make sure that programs function properly in different locales. Hopefully this has got you thinking about your project’s Internationalization and Localization needs and the basic foundation of how it works.